I started out writing an article called How to Split the Bill, but I can’t talk about paying the check without talking about Venmo. And I can’t talk about Venmo without talking about our weird relationship with debt.

Our Venmo behavior is like a limp or a bunion—a compensation pattern we've developed to hobble along as we form new norms. Although Venmo has been around since 2012, and peer-to-peer (p2p) payment technology has existed more broadly since the late 1990s, we’re still adjusting. In just a couple of decades, we’ve gone from cash, to cards, to instant p2p transactions. The etiquette just hasn’t caught up.

In the early years, Venmo set off a moral panic. “Thanks Venmo, We Now All Know How Cheap Our Friends Are” (NYT, 2017), “Venmo Is Turning Our Friends Into Petty Jerks” (Quartz, 2016). But I think that is overblown.

Venmo solves real problems. It’s easier to split utilities with my roommates. It’s simple to divide expenses on my family vacations. It promotes fairness and equality, and reduces petty resentments (although, maybe not, more on that later). But the things that make it efficient also commodify our interactions. Commodification of friendship sounds bad, but it’s actually what we want. We crave legibility and moral relief.

It’s easier to transactionalize our relationships than deal with the moral discomfort of debt.

Moralities of debt

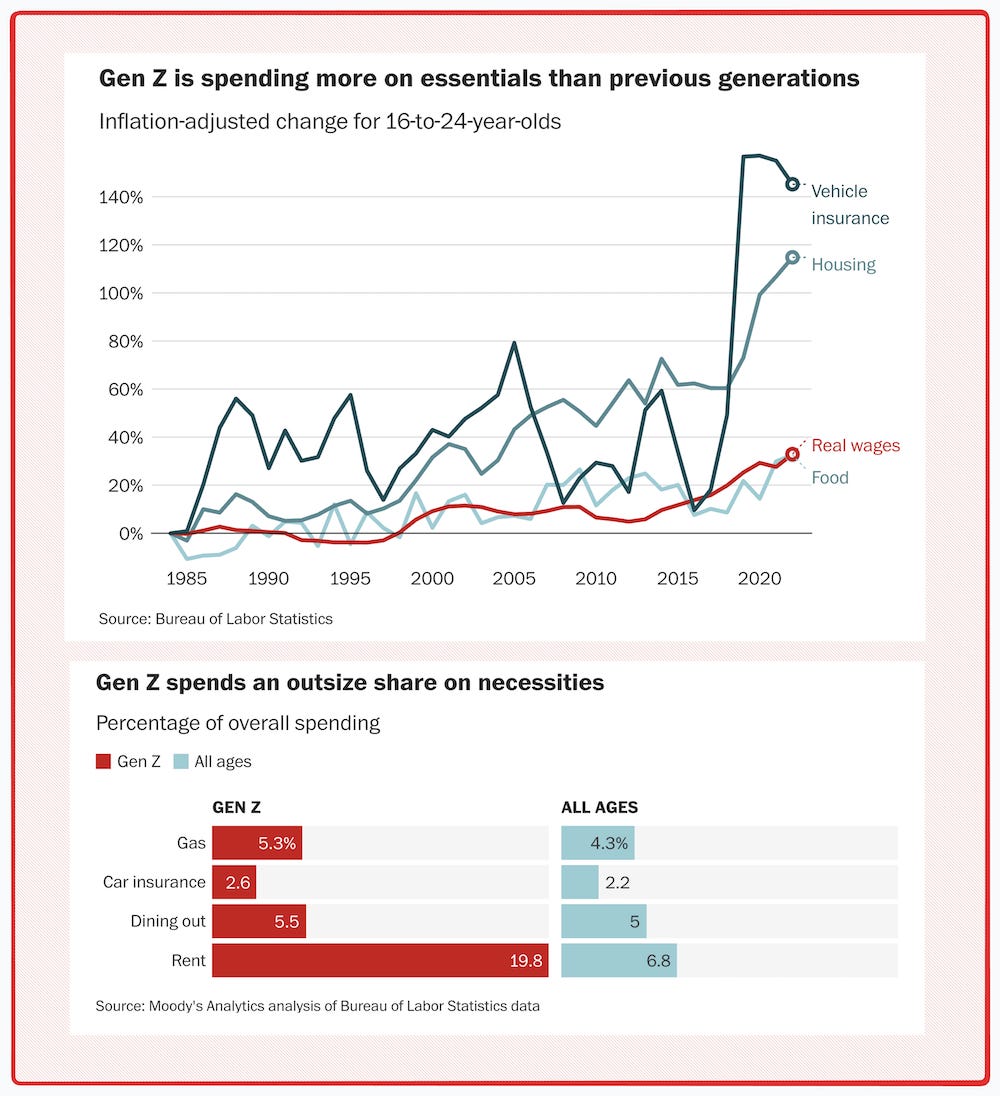

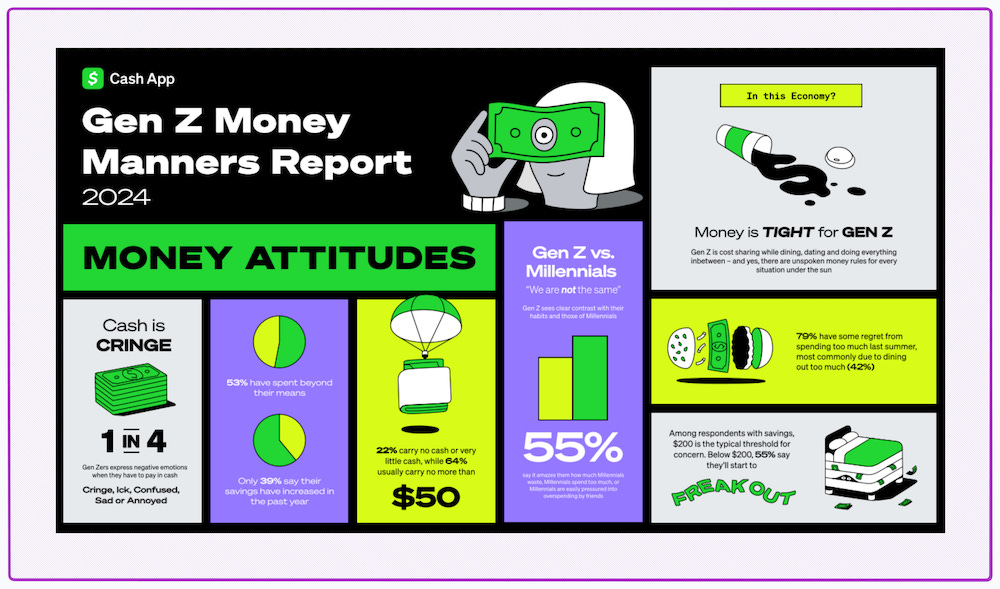

We have a weird relationship with debt. Millennials were thrust into the job market during the Great Recession, carrying huge burdens of student debt, and were ridiculed for living in their parents’ basement. Gen Z is fairing even worse. They carry the highest personal debt (average of $94,101, a majority in credit card liability), and are trying to build their adult lives amidst the sharply rising cost of living. In fact, zoomers pay more for basic expenses like housing and car insurance, double what millennials paid at their age, adjusted for inflation.

Despite these bleak economic realities, both generations have faced relentless criticism: millennials shamed for buying lattes instead of real estate, Gen Z mocked for Shein hauls and lack of work ethic.

In the U.S., debt is framed as a moral failing. Financial stability is a measure of personal character. David Graeber, in Debt: The First 1,000 Years, writes, “Debt and power, sin and redemption, become almost indistinguishable.” According to Graeber, capitalist models transform financial debt into a moral shortcoming, used to justify hierarchy and exploitation.

In his essay The Indebted Man, Maurizio Lazzarato, calls this the “neoliberal condition.”

During the transition from post-WWII strong government (G.I. Bill, Medicare, minimum wage) to neoliberal policies (deregulation, privatization, and reduced government spending), financial responsibility shifted from the state to the individual. By the 1970s, Americans were taking on more personal debt to access housing, education, and healthcare. This neoliberal system, Lazzarato says, creates a cycle of shame and guilt, where we’re always striving to justify our financial choices.

I’m not taking a stance here on whether capitalism and neoliberalism are good or bad (buy me a beer first). I’m interested in discussing their effects. Personally, I feel the moralizing everywhere: in discourse around student loan forgiveness, overconsumption, home ownership, anti- and pronatalism, everything. I don’t have car payments or mortgage debt, but I feel shame for that too. Instead, I’m paying petty debts like old medical bills and credit cards. I see my peer group struggling under this burden, and I see how our struggles are cast as irresponsibility (see: “Gen Z and millennials are ‘doom spending’”).

“These moral dramas start from the assumption that personal debt is ultimately a matter of self-indulgence…redemption must necessarily be a matter of self-denial,” Graeber writes. “What’s being shunted out of sight here is the fact that everyone is now in debt…One must go into debt to achieve a life that goes in any way beyond sheer survival.”

Although debt is an expected part of American life, I feel a deep malaise about it. I rarely talk about it with friends or family. I don’t check in with my brother or best friend on how their principle is shrinking. It’s this silent, shameful burden me and all my peers carry, and we’re looking for ways to relieve the psychological pressure.

The Venmo cope

P2p apps to the rescue. Venmo allows me to neutralize the guilt of owing money by cleaning the slate immediately. In my cycle of anxiety, guilt, and perpetual obligation, I’m trying to acknowledge and compensate for it everywhere. “Oh no, you don’t have to get that!” “How much was that coffee?” “Let me split the Uber with you!”

Keeping a balanced Venmo ledger signals conscientiousness, fairness, and respect. It’s an acknowledgment that I don’t expect friends to carry financial burdens on my behalf. The ledger is clean, and so is my conscience.

By offering a clean slate with every transaction, Venmo eliminates the relational ambiguity of debt. On the one hand, that provides the moral clarity I crave. On the other, it’s robbing me of opportunities to build trust.

What we’re losing

Relationships thrive on small social debts. Uncalculated generosity is an essential building block for trust and durability in friendship. As p2p culture takes over, this dimension of relationships is at risk. But what exactly is at stake?

Anthropologist Marcel Mauss, in The Gift, writes that social debt serves three key functions: trust-building, risk tolerance, and social cohesion.

Trust-building. When a friend covers lunch or helps me move, they trust that I’ll return the kindness in the future. Over time, these repeated exchanges create confidence and deeper trust between us.

Risk tolerance. Informal debt teaches us to tolerate short-term imbalance. I might pick up a bar tab one night, trusting you will do the same later. The amount fluctuates—sometimes $50, sometimes $10—but the long-term balance isn’t tracked, we trust that it will balance out. This faith initiates our innate reciprocity reflex, a psychological instinct to respond in kind, and strengthens the trust needed to take on bigger risks/debts for each other.

Social cohesion. Mauss writes that gift economies are ongoing cycles of giving, receiving, and reciprocating. These cycles reinforce interdependence and belonging. Mutual obligation—the act of owing and being owed—ties people together.

The feeling of obligation is a tricky one. As a debt-anxious millennial I’m freaked out by obligation; I’m striving always for equality and balance. But gift economies operate differently, using debt and power struggle to create group cohesion. It’s an uncomfortable truth, but if you have an outstanding debt with someone, you’re incentivized to continue that relationship until it’s resolved. That feeling isn’t always amicable, but it’s a part of the fabric that holds a community together.

The cost of conflict avoidance

Gift economies have a lot of social benefits, but there are costs, too. Conflict is a big one. Before p2p payment apps, if you owed me money for the bachelorette weekend, I’d have to call you on it. I don’t want to confront you like a repo man in your driveway. Venmo allows me to sidestep this entirely. Personally, I think this is awesome. I hate conflict. Socially, however, I recognize this is a major loss.

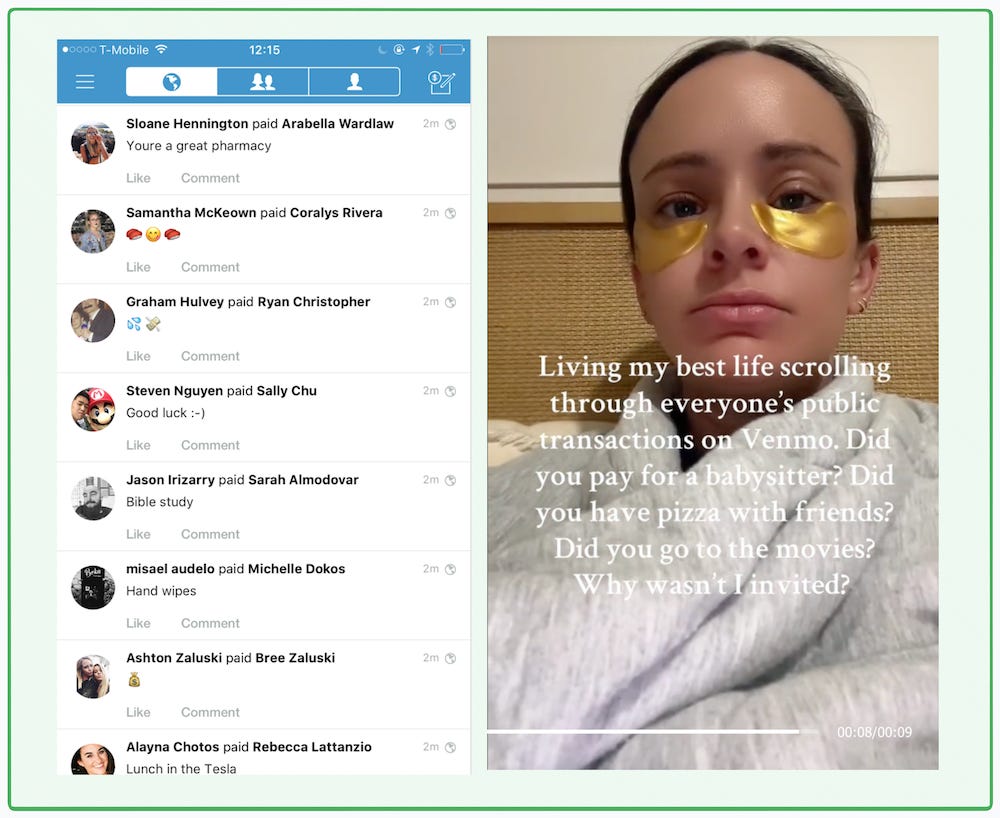

By now, we’ve all had good and bad experiences with Venmo. I love getting $7 from a friend who knows I’m having a bad day, “Get yourself a boba tea, ily.” It turns my whole week around. But then there’s the surprise $2 charge for the basket of fries I split four ways at the bar, or the $10 charge for gas after a friend took me to the airport. This woman received a $6 request for the glass of wine she had at a friend’s house. This friend was charged for ingredients after attending a dinner party. The audacity is next level because the consequences aren’t as costly.

Instead of having direct conversations about money, Venmo is atrophying the social skills we need to manage financial expectations and have constructive confrontations.

After avoiding it for weeks, I recently had to confront a friend about a debt. A Venmo reminder would have felt spineless, so I took a deep breath and said, “Hey, you still owe me for the hotel.” That moment was awkward, but it legitimately strengthened our friendship. She said, “Oh shit, you’re right.” She confided about her current financial precarity, and we renegotiated that she could venmo me once she got paid on Friday. My trust in her was renewed, and she appreciated the honesty and accountability.

If I had sent a Venmo reminder instead, she would have felt attacked, and we would have both stewed in silence, growing resentful.

This sounds judgmental, and I’m sorry. I’m just as guilty of Venmo passive aggression as you. But if we continue outsourcing financial conversations to an app, we risk losing the ability to handle conflict, navigate generosity, and maintain honesty in our relationships.

Friendships as ledgers

Venmo is, at its core, a friendship ledger. Critics worry that it commodifies relationships—especially through the social feed—but tracking debts, both financial and emotional, isn’t new. We already keep mental tabs on generosity: who remembers birthdays, who checks in after a breakup, who always asks for favors but never returns them. These exchanges shape trust and reciprocity.

What is new is the way Venmo makes only the monetary aspects of friendship explicit. The friend who always replies to my tweets or never misses my spin class is racking up social credit—but if I tried to quantify it, that would be destructive and insulting. Friendships are multi-dimensional; acts of care, support, and effort aren’t transactional.

That’s why I don’t think Venmo’s public feed is harmful in the way critics fear. To be honest, I think the public feed is creepy and voyeuristic, but whatever, publicly marking a debt’s repayment gives the gesture gravitas and accountability. The feed may be performative, but it’s just a gamified version of something that has always existed. Plus the legibility of Venmo is a relief—it removes the cognitive load of tracking who owes whom, making it easier to maintain balance without resentment.

The danger of Venmo as a public ledger is that it flattens the many dimensions of friendship into one measurable one. It makes the monetary debts explicit and pushes the intangible ones—emotional support, reliability, showing up—out of sight.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

Making new norms

I want to underline one thing. It’s okay if you feel weird about debt. Feeling guilty and judged sucks and it’s fucking unfair. We’ve been conditioned to see financial independence as morally good, and financial dependance as morally bad. The tragic part is that we’re transferring this judgment to our personal relationships. We’re trying to settle the anxiety and shame we feel about a systemic issue by performing financial morality to our friends.

But that’s simply not going to work. As Graeber reminds us, the financial system doesn’t care if you always venmo Ted back for brunch. We can’t allow the convenience of Venmo to train us into transactional vigilance. Not every favor, act of generosity, or moment of social connection must be reconciled.

We need to build more space for uncalculated generosity, to recognize that social debt—the kind that deepens trust, fosters connection, and coheres community—cannot and should not be zeroed out. The instinct to settle everything immediately is not a sign of moral hygiene; it’s a sign that, as Lazarrato writes, we’ve internalized the guilt that belongs to the system, not the individual.

If we use Venmo as a cope, we risk atrophying our muscles for risk tolerance and relational ambiguity. But if we use it in more prosocial ways, we can reclaim its utility for generosity. I believe we can co-opt this trust-corroding technology and use it in ways that incentivize connection over transaction.

Stay tuned for part 2, where I’ll lay down new rules of Venmo etiquette—when to use it, when to avoid it, and how to split the bill elegantly no matter the payment method.

You’re reading Season 3 of The Ick. The social rulebook has been rewritten in our post-pandemic world—and it's left us wondering, “Am I doing this right?” Season 3 of The Ick is creating a modern field guide to social etiquette and decoding the hidden architecture of human connection. Subscribe here. Find season 1: embarrassing stories here, and season 2: the five senses here.

So excited for part 2! Was it you who told me about how barter culture was more like a social debt than a one for one trade? Like, it wouldn’t be one chicken for one cabbage, but one chicken for future cabbages and/or whatever I might need. People who did not put in their share would be censured by the collective.

Yes!!